back to blog

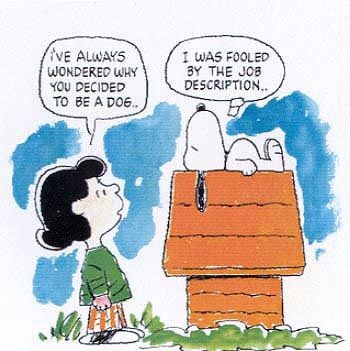

Why We Banned Requirements from Our Job Descriptions

Our co-founder's memo on Luminovo's performance-based hiring philosophy and why we chose to redefine our hiring process.

April 27, 2020

What follows is a memo I wrote to explain the hiring philosophy at Luminovo to our team. If your job descriptions still include a list of skills and experiences (like “X years of Python experience” or “a university degree in communication design”) you might benefit from reading this. As it was originally written for internal training purposes, there are some references to Luminovo that you can happily translate to your own company while reading. I hope this will help you put your own hiring process on a sound footing.

Purpose

This document serves to explain the philosophy of performance-based hiring that our hiring process is based on and includes advice and specific suggestions on how to put that philosophy into practice. Among other things you will learn about performance profiles, the opportunity gap and the two types of questions.

It is meant to be read and discussed by everyone involved in recruiting new talent.

Other Resources

Most of the content of this document is based on the book Hire With Your Head by Lou Adler.

_____

Performance-Based Hiring

“Teamwork makes the dream work.” – Some person with a knack for rhyming.

We need to hire and retain top talent. It is the single most important factor underlying all of our (potential) success. To do this consistently and to avoid hiring mediocre team members is the goal of the performance-based hiring process.

As the name suggests performance-based hiring leans on assessing how an applicant’s past performance lines up with the desired performance on the job. In other words: can this candidate get done what we need them to get done?

Asking this question might sound obvious, but most hiring processes do not actually put their focus on this. Instead they often ask if a candidate has skill A or skill B, how many years of Python experience they might have or what their university degree is. But focussing on what the applicant needs to get done as opposed to what skills they have offers some key advantages:

1 – It puts a focus on the opportunity gap.

2 – It mitigates expectation mismatch between employer and employee.

As you will probably experience for yourself writing good performance profiles is hard. It’s hard because often times you haven’t really thought that much about what a person will need to do once they start. To avoid bad surprises for either side it’s a good idea to clarify this as much as possible before a person starts rather than after they do.

3 – It leaves more breathing space for unorthodox applicants.

Sometimes we might not know exactly (or have misguided ideas of) what skills someone needs to have to achieve our performance objectives. By putting a focus on what the candidate will need to get done, we put the focus (by definition) on what matters most to succeed on the job. Another way to look at it: if someone can do what needs to get done, they probably have the skills they need to do what needs to get done. Who cares if they have an Ivy League degree.

Performance Profiles

Embarking on the journey of finding a new Luminerd always starts with writing their performance profile.

While normal job descriptions will often have a long list of requirements (like skills, experience or academic laurels), the best people don’t get excited when they see a list of skills they already possess. Instead a performance profile should focus on what the candidate needs to do to excel in their position. The challenges that our job opportunity comes with is what the best people are interested in and that is what the performance profile should focus on. A good way of thinking about the concept of a performance profile is simply to reframe the role into a “success profile”. You should ask yourself: What does a person need to do in this role in order to be considered successful?

A performance profile consists of a list of performance objectives. Each performance objective should define superior performance and clearly state what needs to get done on the job. Instead of focusing on what people need to have, it should focus on what people need to do.

A job description telling us that you are looking for a “good communicator with proficient Python programming skills and a Master’s degree in Machine Learning” distracts from what we ultimately care about (on-the-job performance), might exclude good candidates and it often is an artifact of lazy thinking demonstrating that you do not yet clearly understand what a new hire will need to do to succeed in the role you are looking to fill. A good performance profile for this role will have performance objectives describing what this “good communicator” you are looking for will need their communication skills for and what outcomes they will need to produce with their Python and Machine Learning experience. Two possible objectives could be:

“Implement and tune state-of-the-art ML models to get the best possible results given a dataset and metric to optimize”

“Effectively communicate and document your approach, progress, results and challenges both within the team and towards our clients”

For more advice on writing good performance objectives, see the Appendix (Writing Performance Objectives).

After reading a finished performance profile the candidate should know exactly what will be expected of them once they join the company. A good performance profile can serve as an on-boarding document and as the basis of future performance reviews. And it does not stop there! The logic of writing performance objectives and understanding a person’s opportunity gap can be used to continuously “rehire” people within your company and get them psyched for the next step they and your company will take.

Note: We often include some bullet points that are not proper performance objectives in our performance profiles (“attend insight hours and fun team events”). Their purpose is to illustrate that Luminovo is an awesome place to work at. Do not confuse them with proper performance objectives.

The Opportunity Gap

Remember: our goal is to retain and hire the best people. But the best performers screen differently for a job than the average performer. For the best (like you, dear reader 🤗), each new job is a strategic decision they evaluate based on what they can achieve and learn both in the short-term and the long-term.

This gap between what an applicant does now and what they could be doing in the future if they take the job is called the opportunity gap. It consists of job stretch (immediate responsibilities, tasks and challenges that are new to the applicant) and job growth (long-term growth prospects we can offer) and is the best way to motivate the best people for a new job.

Understanding an applicant’s opportunity gap is key to making sure they are right for the job and the job is right for them.

Note: The belief that the opportunity gap motivates the kind of people we want to work with is actually embedded in our operating principles (Keep Learning. Focus on Impact.).

_____

Interviewing

“Interviews should be a fact-finding mission, not a popularity contest” — Lou Adler

The first thing to keep in mind when starting to interview a candidate is that there is little correlation between interviewing skills and on-the-job performance. We want to use on-the-job performance as our selection criterium not interview performance.

The second thing to realize is that the interview is there to collect information, not to make a decision. Often people tend to make a gut decision only a few minutes into the interview. Force yourself to delay the decision as long as possible! And work against your intuition. A bad first impression should be an invitation to find facts that prove you wrong (and the same goes for a good first impression).

By now we have defined what our candidates will need to do on the job (thanks to our performance objectives) and we have agreed that we ultimately care about on-the-job performance (as opposed to interview performance). Time to start the seemingly black magic process of trying to predict the future of how well a candidate will do their job.

Predictors of Success

At the core of performance-based hiring is the belief that the best predictors of success for on-the-job performance are not skills, but energy, talent and comparable past performance.

The energy a candidate brings to your company largely depends on their motivation to do the work that needs to get done and to understand a candidate’s motivation you need to understand their opportunity gap. Talent will impact how much time the candidate will need to bridge the opportunity gap and the best way to think about it is in terms of comparable past performance. The most talented applicants will have a consistent track record of exceeding expectations in the things they have committed themselves to doing.

This leaves us with comparable past performance and fortunately there are only two types of questions you need to know about to understand this predictor of success.

Two Types of Questions – The MSA

The first question is called the “Most Significant Accomplishment” question. It arises naturally from a good performance profile and goes something like this: “As a fill-in-role-title-here you will have to fill-in-performance-objective-here. Can you tell me in detail about the most significant accomplishment that you believe has prepared you to do this well?”

Instead of going broad and brushing over all the things they have ever done, you want to dig deep into their most significant accomplishment. What was the situation you faced when you started the project? What were the biggest challenges you had to overcome? What were the results obtained? What skills were needed? What skills were learned? What was your role and who did you work with? What would you do differently?

Fact-Finding

All of the follow-up questions above are examples of fact-finding. Without fact-finding asking the MSA is worthless. Doing good fact-finding lies at the heart of performance-based hiring. If you just let the interviewee tell you about their accomplishments without doing fact-finding, all you will be doing is measuring interviewing skills (the thing we set out to avoid in the first place). Fact-finding is great because it works two ways. On the one hand, it helps uncover candidates that are good at interviewing and inflating their achievements of the past. On the other hand, even candidates that are bad at interviewing (say they get very nervous in interview settings) are good at talking about things they have spent a lot of time doing and know in-depth. It lets you go past interviewing skills and helps you to truly understand their comparable past performance.

As you get better and better at fact-finding, you will realize that to conduct an insightful interview all you need is the MSA question and a very good understanding of the job the candidate will need to do (as summarized in the performance profile). As you can ask the MSA about any performance objective, it is usually a good idea that everyone involved in the hiring process coordinates before the interviews to decide which interviewer will focus on which of the performance objectives in their line of questioning.

Comparable

You might have noticed the implicit tension between a candidate’s opportunity gap and their past performance. More and better examples of past performance imply a smaller opportunity gap which will negatively impact their motivation to do the job.

The key to resolving this issue lies in the word comparable. You want your candidates to have comparable past performance, not necessarily identical past performance. Comparable accomplishments can be made by doing something different in a similar setting or doing something similar in a different setting.

When we write performance profiles we try to avoid making too many assumptions about what skills are needed to do the job at hand. In the same spirit, we want to leave the choice of what a comparable accomplishment can be to the candidate when we ask the MSA question.

Don’t sell (too much)

“Recruiting is more about buying than selling. If you sell too soon, you stop evaluating. If the job is compelling, candidates will sell you as they attempt to convince you why they’re qualified.” — Lou Adler

Every interview is a two-sided affair of the applicant convincing us and us convincing the applicant that they should be working for Luminovo. The best people are interested in working with great teammates and this holds true for you (the interviewer) just as much as for the interviewee.

However, you cannot tell a person straight off the bat how great a job is. They need to learn for themselves. If a job seems too easy to get, it becomes uninteresting. So do not start selling (yourself, the job or the company) too soon, even if you are convinced of an applicant’s qualifications.

Rather spend the interview talking up the opportunity gap. Everyone is proud of their accomplishments, so the optimal interview is one where you get the candidate to see the job opportunity and they starts trying to sell you their skills and relevant experience.

You can do this by using the recruiting and challenging questions technique during the interview. It goes like this: Use your questions (and the lead-up to it) to challenge the candidate and talk up the challenges they will be facing on the new job (“Your experience with X is really impressive, but I feel you have not had the chance to do a lot of Y. Can you tell me more about related accomplishments that might qualify you for this new challenge?”). The MSA question is a natural fit for this questioning technique.

Two Types of Questions – The Jam

What is even better than asking about comparable past performance? Seeing comparable live performance, right there in the interview! In a jam you just take a problem that the person will face in their new role and ask how they would go about solving it. The closer you can approximate the real-world setting the better. A jam is meant to be a collaborative session where you hash out the solution in a back and forth between interviewer and interviewee.

Starting the Interview

It is usually a good idea to start the interview by outlining what exactly you will be doing in the interview in what order and telling them about which performance objectives you think are the most important for the role.

During the Interview

Make sure you listen more than you talk. After asking a question resist the urge to fill an awkward silence. Instead wait and give the candidate time to think and answer.

Ending the Interview

End the interview by giving the candidate 10 minutes to ask their questions. At the very end close the interview with a question like this: “Although we’re seeing some other fine candidates, I personally think you have a very strong background. We’ll get back to you in a few days, but what are your thoughts now about this position?”

It creates competition (without this great candidates can quickly lose interest and you strengthen their negotiation position later on if you tell them flat out that they are one of the best candidates you have seen), demand (express sincere interest — people will think more about why they want a job when told they are well liked and qualified; with a neutral or negative ending people will go away thinking about why they are not going to get it) and surfaces concerns on the candidates side early on by asking them about their first impression.

A Note on Cultural Fit

Many recruiting processes put an active focus on “cultural fit”. Would I like to grab a beer with this person? I agree that cultural fit is a factor that is crucially important. But cultural fit in the sense of “do I like this person” does not deserve any extra attention, since we would never hire someone we do not like anyways. Interviewing is hard and needs to be learnt, but judging whether you like someone is easy and every new interviewer already comes with years of practice. Try to determine whether you like a candidate, only after you have determined their competency.

There are of course some parts of cultural fit (like giving pro-active feedback and valuing psychological safety) that we should be checking for and for these we have our operating principles (or you could think about them as value objectives) that (just like performance objectives) focus on what people do as opposed to what they have.

_____

Appendix

Writing Performance Objectives

A good performance objective should:

Describe the results needed by the candidate to be successful, key process steps to achieve these results and give an understanding of the environment (like pace, resources, professionalism and decision making processes).

Convert having into doing, technical skills into results. Use active verbs not passive ones (“be responsible for” is passive!).

Be SMARTe.

Specific: Include the details of what needs to be done so that others understand it.

Measurable: It’s best if the objective is easy to measure by including amounts or percent changes.

Action-oriented: Action verbs build, improve, change, and help understanding.

Results: A definition that complements the measurable piece by clearly indicating what needs to happen.

Time-bound: Include a date or state how long it will take to start and complete.

environment: Describe the company culture, pace, pressure, available resources, and politics.

If you are hiring a role that is already being done in the company, the best way to go about writing a performance profile is looking at what the best people in that role at Luminovo do and what sets them apart from the average performer.

Last but not least, a good question to ask yourself while writing a performance objective is the following: if you posed the MSA question about this objective, could you imagine getting specific examples of what they have done in the past from your candidate (that’s good!) or would you expect it to lead to very vague answers? (that’s bad!).

A common pitfall

The most common pitfall I see with POs written at Luminovo is just spelling out what the candidate will be doing instead of defining what superior performance looks like.

Often this can be fixed by adding a measurable result to the PO, but anyone who has spent some time writing OKRs knows finding good key results can be challenging. Even if you do not have a measurable result to bolster your PO, you should still make sure you define superior–not just average–performance. Without a measurable result it is critical that you provide enough context on why what the candidate will be doing is important. It will help people reading the PO infer the difference between good and great.

A legal perspective on writing performance objectives

In Germany, it is (thankfully so) illegal to discriminate against applicants based on age (also gender, ethnicity, sexual preferences, religion or disability). Thus, if you are a young and dynamic startup looking for a “young and dynamic team member” you are putting your company at risk of being sued. If you write performance objectives instead of job requirements and focus on what people do as opposed to what they have or who they are you are much less likely to end up discriminating in your job descriptions (be it by accident or not).

____

Thanks to Erin Bacsy and Patrick Perner for your feedback on the first draft and putting our hiring philosophy into practice every day. 🤗 Thanks to Sebastian Schaal for indulging the good and keeping in check the bad ideas I have for rethinking how we do things at Luminovo every day — and for knowing which is which.

If you have feedback, thoughts or think any of this is bad advice, I would love to hear from you.

Book a free demo

Let our product specialists guide you through the platform, touch upon all functionalities relevant for your individual use case, and answer all your questions directly. Or check out a 5-min video of the most relevant features.